Can Humans Devise Practical Safeguards That Are Reliable Against an Artificial Superintelligent Agent?

If superintelligence emerges, it will still operate within the constraints of computation, information theory, and physics.

by Michael J. D. Vermeer and Chad Heitzenrater

Much of the conversation around artificial superintelligence (ASI) assumes a kind of inevitability and fatalism. Once AI far surpasses human intellect, the story goes, it will be all but omnipotent—capable of escaping containment, rewriting its own code, and manipulating the physical world to achieve its goals. This view is captured in the book, If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies, and the conclusion is that we have no tools that could reliably avert that grim end.

In our recent RAND report, Can Humans Devise Practical Safeguards That Are Reliable Against an Artificial Superintelligent Agent, we reframe this discussion around a hypothesis that reliable safeguards against ASI are both sensible and feasible. This is not a claim that perfect defense is possible, but that fundamental limits rooted in scientific and engineering constraints could give us tools to engineer security that even the most capable AI would struggle to overcome and therefore might be sufficient to provide effective security.

Bridging AI Safety and Security Engineering

Our work aims to act as a bridge between the AI security community and the security engineering community. Researchers who study artificial general intelligence (AGI) and ASI often focus on alignment, control, and existential risk; those who build secure systems focus on measurable safeguards, protocols, and reliability. Yet both groups confront the same question: how to design systems that remain dependable in the face of powerful, adaptive adversaries.

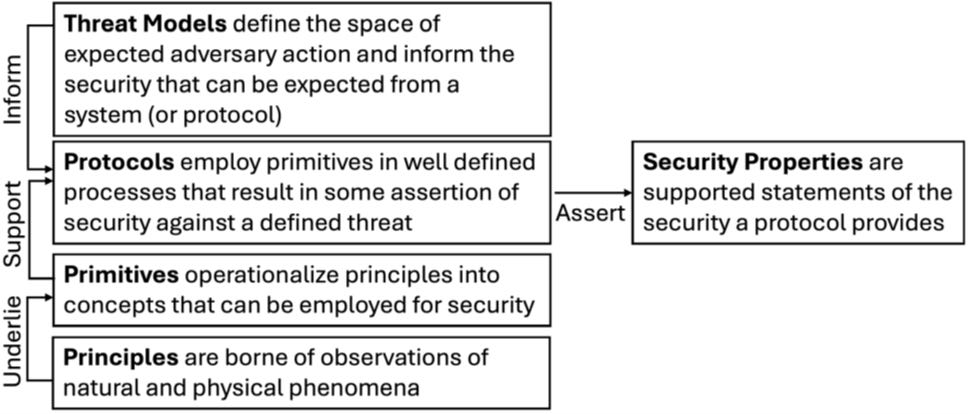

We frame the problem using the same components that underpin all of modern cybersecurity and security engineering—primitives, protocols, practices, and threat models. Primitives are the basic building blocks grounded in physics or mathematics. Protocols define how those primitives interact. Practices add real‑world constraints that keep protocols usable. And threat models describe precisely what the attacker can do. These elements let us reason rigorously about what “secure enough” means. By applying these longstanding ideas to superintelligent AI, we can begin to treat “ASI security” as more of an engineering discipline, and less of a metaphysical debate.

Building on Fundamental Limits

Our approach builds on prior RAND work identifying fundamental limits that even a superintelligence can’t overcome, from which we identify specific limits rooted in computational complexity, information theory, and manipulation of the physical world. Together, we hypothesize that these limits are a basis for defining potential ASI security primitives—foundational phenomena that could underpin robust safeguards even against a vastly intelligent attacker.

We also explore humans as side channels—attack vectors that bypass security protocols. Some analysts assert that a highly capable AI might attempt persuasion or deception to bypass controls through human intermediaries. We hypothesize that human persuasion is not assured, and relying on human persuasion introduces uncertainty and likelihood of detection. Moreover, controls like multi-party authorization and shared-secret schemes can be implemented to make this attack vector harder for the AI adversary.

Turning Limits into Strategy

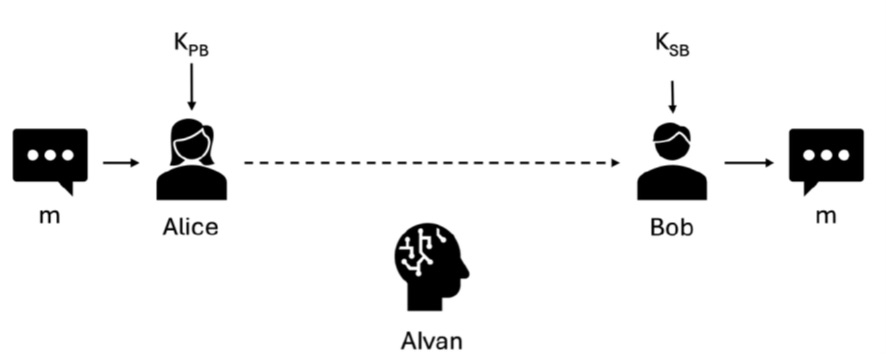

To illustrate how these ideas might translate into action, we describe a simplified scenario: two people—Alice and Bob—communicating while an AI adversary named AIvan seeks to intercept their message.

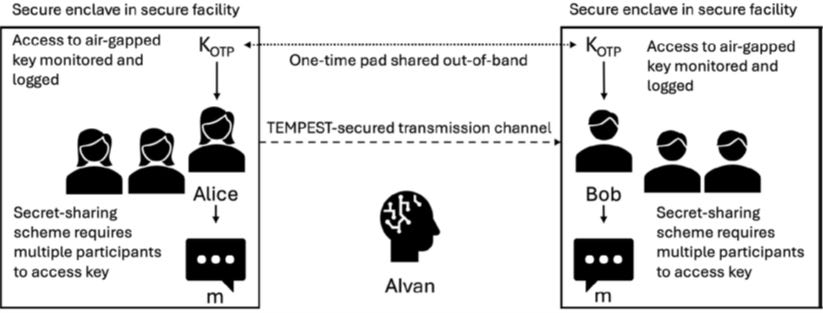

As AIvan’s assumed capabilities escalate—from discovering stored keys to inventing new physics—the defenders respond by layering controls. They move key material offline, employ faraday shielding, adopt post‑quantum algorithms, and, finally, rely on a one‑time pad generated from true randomness. Each layer builds on the limits of computation, information theory, or physical manipulation; each imposes greater cost on the adversary.

At every assumed step in the ASI threat model, the challenge from AIvan grows. Even if absolute protection remains impossible, the defenses force the attacker to expend more time, compute, or energy—and crucially, they increase the chances of detection. The human defenders gain breathing room to observe, respond, and adapt. That is the essence of practical security against ASI: not invulnerability, but deliberate cost imposition on an extremely capable adversary, while maintaining systems that are still usable for people.

Hypothesis: All Is Not Lost

Our central hypothesis is rooted in realism, not resignation. Perfect containment may never exist, but robust safeguards anchored in physical and mathematical limits might deny, delay, and expose malicious actions even from a superintelligent AI agent. Security engineering has always accepted imperfection—it deals in probabilities, trade‑offs, and defenses that buy time. Those same principles will continue to apply. If superintelligence emerges, it will still operate within the constraints of computation, information theory, and physics. Are these fixed points that we can design around? Rather than treating intelligence as omnipotent, we should view it as another threat model—extraordinarily capable but still bounded.

The work ahead is to formalize and test this hypothesis, to bring security engineering and AI communities together to explore whether we can turn abstract limits into concrete protocols and practices. But for now, one conclusion is clear: human ingenuity, grounded in science and engineering, still has room to make a difference.